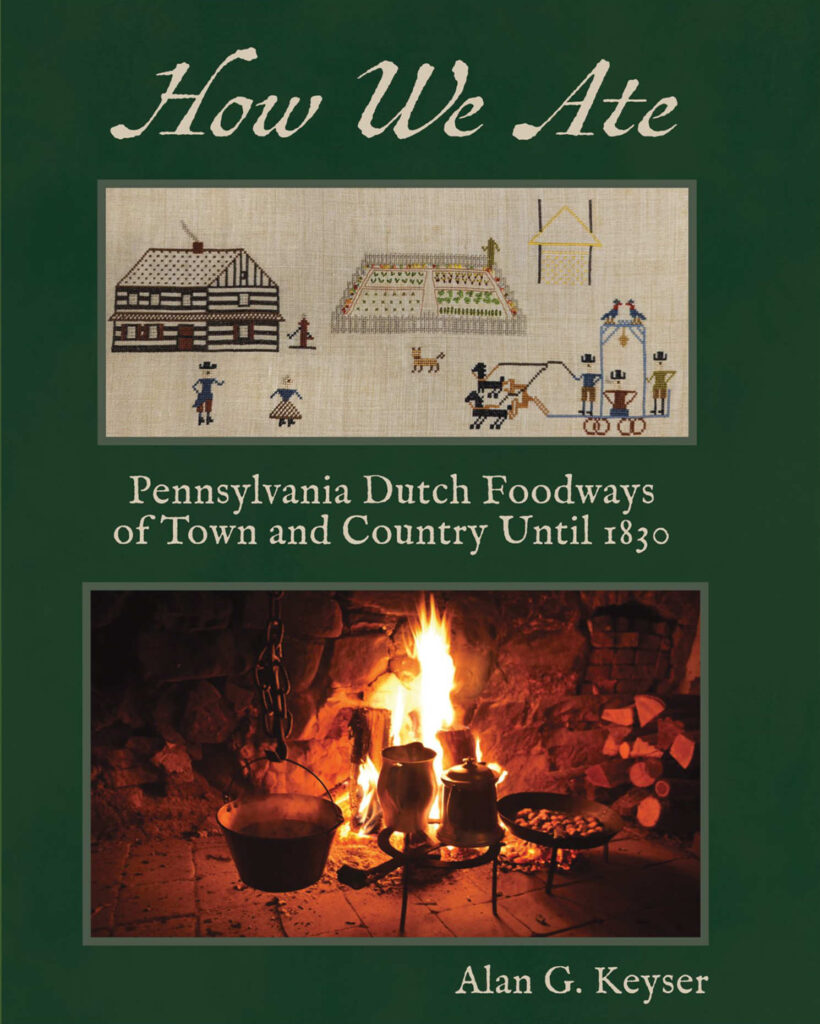

Book Review: “How We Ate: Pennsylvania Dutch Foodways”

Historical research is challenging, especially when it is on a niche topic like our Hagenbuch family. Good sources are few and far between and, when you do find something, it is often incomplete.

Earlier this year, Chris Witmer—who previously took my father, Mark, and I to a number of Deitschy sites—asked if I had obtained a copy of a new book, How We Ate: Pennsylvania Dutch Foodways of Town and Country Until 1830. I hadn’t and, when I went to find a copy, I learned that it was sold out. How disappointing! I added my name to the wait list for the second printing, which was organized by the publisher, the Schwenkfelder Library in Pennsburg, Pennsylvania.

How We Ate was written by Alan G. Keyser. It is the culmination of over 40 years of research into the customs, culture, lifestyle, and food of the Pennsylvania Dutch. If Keyser’s name looks familiar, this may be because you have seen him credited on this site. Previously, he helped to translate Hagenbuch family documents that were recorded in the Pennsylvania Dutch language. More about that in a minute.

At almost 700 pages long, Keyser’s book is a deep dive into how Pennsylvania’s Dutch (Deitsch) people lived, cooked, and ate between the years 1700 and 1830. Yet, it covers much more than food. The book opens by describing how German immigrants arrived in colonial Pennsylvania, cleared land, and built homesteads. It examines the tools, cookware, and furniture they used, connecting these with the foods enjoyed by the Pennsylvania Dutch.

The book is filled with ingredients, cooking instructions, and recipes found in primary source manuscripts. That said, How We Ate is not a cookbook. While it does include some recipes that could be easily made today, Keyser’s focus is on the history, process, and original directions for making various foods.

For example, one section reports how in 1799 George Carothers of Lancaster advertised ice cream for sale and how several other people in Reading did the same. Keyser analyzes the ads and mentions that they did not state the ice cream flavors. However, his research suggests that fruit flavors, such as lemon, were popular at this time. He explains that vanilla ice cream didn’t become popular until the second half of the 19th century. Keyser doesn’t touch upon why that was, although further research reveals that mass cultivation of vanilla only started in 1841 after twelve-year-old Edmond Albius (b. 1829) discovered how to pollinate vanilla flowers by hand.

Black and white photograph of a painting of Sarah Shippen (Burd) Yeates, c. 1820. Credit: The Frick Art Reference Library

Hagenbuchs love ice cream, and the closest thing to an ice cream recipe within How We Ate is taken from a period cookbook written by Sarah Yeates. Keyser quotes her instructions for putting a smaller pewter basin inside a larger one, then filling the larger one with ice and salt. Next, the inner, smaller basin is filled with cream, sugar, and fruit—like raspberries. A lid is placed upon the top of the inner basin. Every hour, the lid is removed and the ice cream is stirred with a spoon until it reaches the right consistency.

One critique of Keyser’s writing is that it doesn’t always provided comprehensive detail for its primary sources. For instance, Sarah Yeates instructions for making ice cream don’t note where or when she lived. Research shows that Sarah Shippen Burd was born in Lancaster, PA in 1748, and that she died in 1829. She was married to Captain Jasper Yeates (b. 1745, d. 1817), who was a Pennsylvania Supreme Court Justice and active supporter of the American Revolution. Facts like these would further enrich Keyser’s book. However, it is understandable why he omitted them, given the time need to expound upon each person, place, and source.

The book is divided into 16 chapters. Starting with an general introduction of the Pennsylvania Dutch style, history, and customs, it segues into a look at the implements, tools, cookware, and tableware of the home. Next, the text examines how the Pennsylvania Dutch acquired foods at market and chronicles the meals that were served daily. Sacred and secular holiday food customs are explored, in addition to seasonal choices for cuisine.

A majority of the book focuses on how the Deitsch people acquired, prepared, and ate various types of food. These include individual chapters about spices, flavors, and condiments; rye in cooking and bread making; cakes, pies, and pastries; a plethora of meats such as beef, pork, scrapple, poultry, and lamb; fruits, nuts, and vegetables like cabbage, which was fermented into sauerkraut; milks and cheeses; beverages like coffee and tea, along with alcoholic drinks like applejack and rye whiskey; and soups served either cold or hot.

Keyser’s book is a tour-de-force of the Pennsylvania Dutch cuisine enjoyed prior to the Civil War. While other authors like William Woys Weaver have written Deitschy cookbooks rooted in historical sources (see the recipe for Forty-Nine Beans), they sometimes update these with modern directions and modify them to appeal to current sensibilities. Keyser’s book, although more challenging to cook from, provides a truer sense of exactly what and how our earliest Hagenbuch ancestors ate in America.

As mentioned earlier, Alan Keyser previously helped to translate a number of historic documents that were featured on Hagenbuch.org: the 1783 plans for Christian Hagenbuch’s (b. 1747) home, the 1842 inventory for Jacob Hagenbuch’s (b. 1777) estate, and Timothy Hagenbuch’s (b. 1804) letter to his brother, Enoch, from 1851. One of the most exciting parts of How We Ate is that Keyser used some of these translations in his book!

When discussing the design of an 18th-century Pennsylvania Dutch home, Keyser refers to the plans for Christian Hagenbuch’s house. Later, as he explains various beverages consumed by the Deitsch, he mentions how Christian willed that his wife, Susanna (Dreisbach) Hagenbuch, receive an annual supply of coffee, sugar, and tea. Keyser also demonstrates that Christian was concerned for his wife’s well being. In his will, he asked that his sons Andrew (b. 1782) and Joseph (b. 1795) provide their mother with “firewood cut ready for use and laid down at the door.” What a wonderful bit of Hagenbuch family history!

Alan G. Keyser’s book How We Ate is a must have for anyone interested in Pennsylvania Dutch culture and, for Hagenbuchs, is a terrific resource for understanding how our ancestors lived, as well as what they ate. Softcover copies can be purchased through the Schwenkfelder Library by downloading this form and mailing it along with payment. The book is $60 plus tax and shipping. Given all the book has to offer, it is all but certain to inspire future articles for this site.