Establishing the Hagenbuch Homestead

In the spring of 1738, Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1715), his wife Maria Magdalena (Schmutz), and their infant son, Henry (b. 1737), settled on a swampy 200 acre parcel in the Allemaengel region of Pennsylvania. This was a wild land nestled in the foothills of the Blue Mountains. Today, the property can be found within the boundaries of Albany Township, Berks County, PA. Read about the Hagenbuchs acquiring their first land warrant.

We can imagine the Hagenbuchs arriving in the Allemaengel and discovering their parcel wasn’t where they had hoped to build their homestead. They may have tried to hack out a living there for awhile, as they explored the area and searched for other open land. Alternatively, they may never have settled upon the 200 acre parcel and immediately squatted upon another lot until they applied for a warrant.

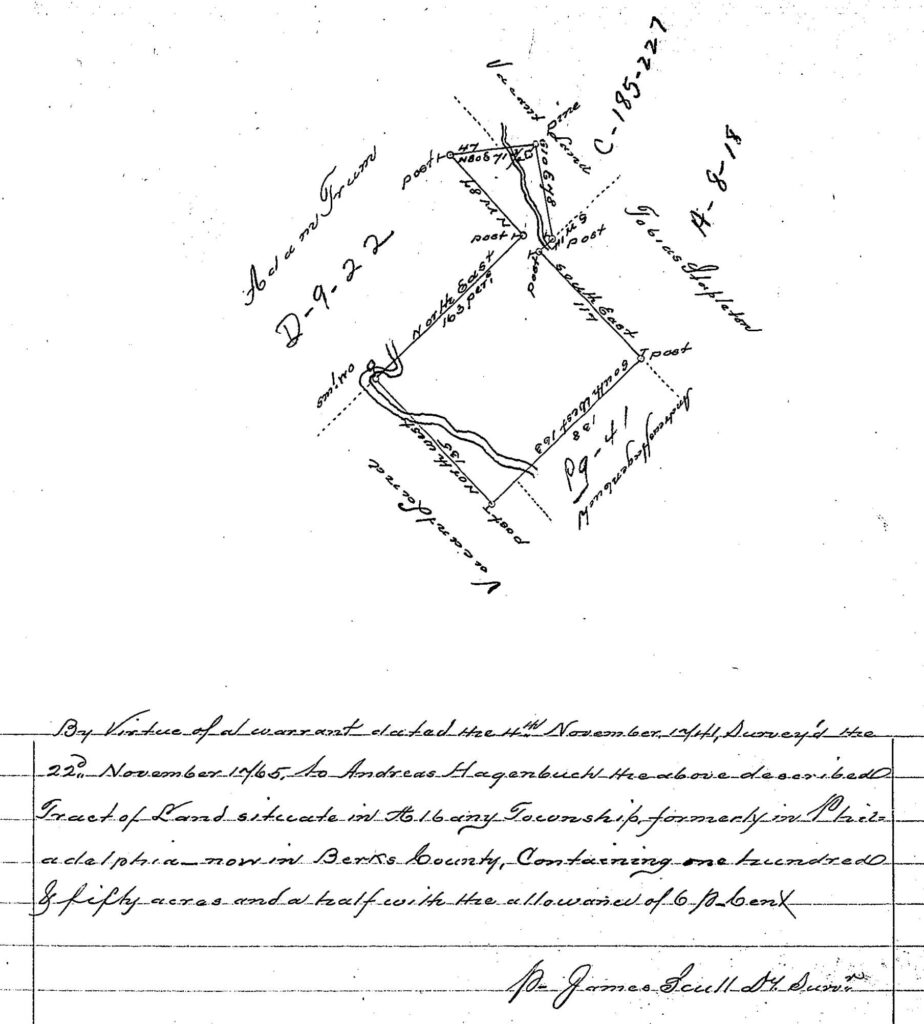

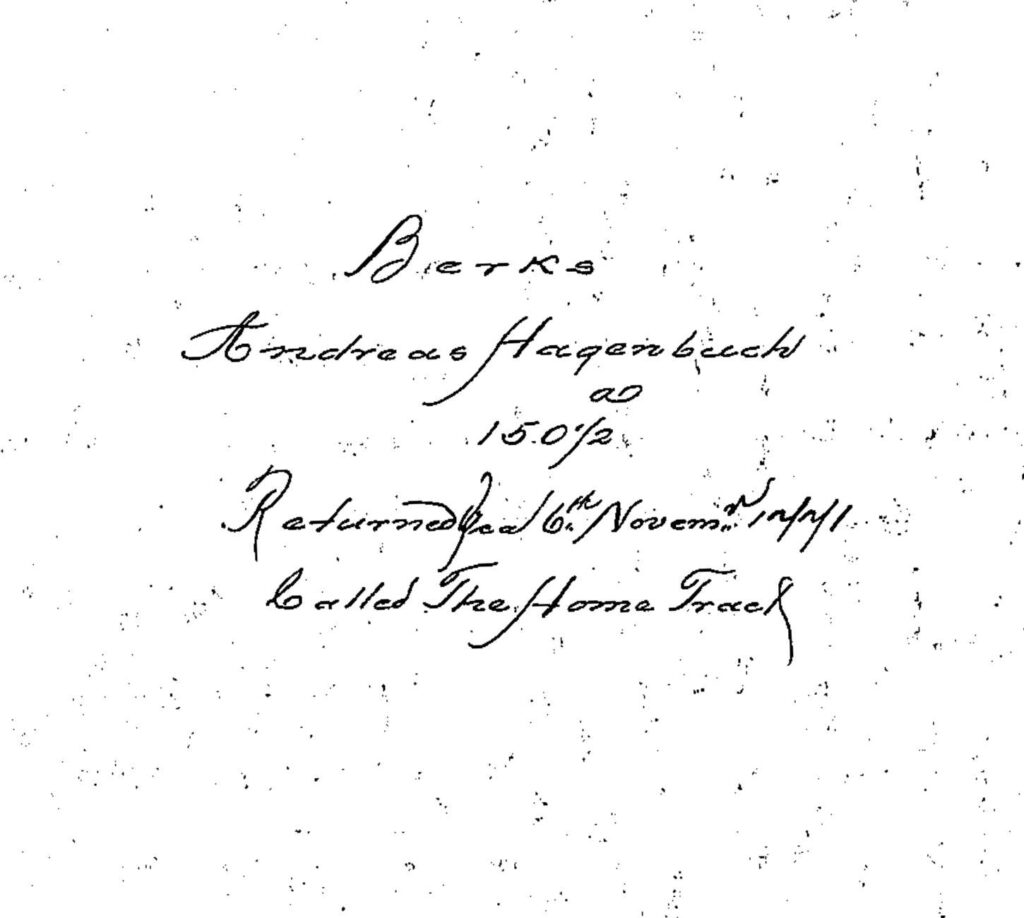

What the records show is that by November 4, 1741, the Hagenbuchs had moved a mile west. On that date, Andreas received a new land warrant for 150.5 acres, although the official survey of the parcel would not be completed until November 22, 1765.

It is worth noting that the surveyor of the land was James Scull. James was the son of Nicholas Scull II, who had surveyed the Hagenbuch’s 1738 parcel. The Scull family had built a profitable business surveying land for settlement. The Scull name can be found on many early surveys completed in this region of Pennsylvania during the mid-18th century.

Also, by the time the survey of Andreas’ land was completed in 1765, Berks County and Albany Township had finally been established. These are both mentioned on the survey. When the original land warrant was issued in 1741, the parcel was still within Philadelphia County. The survey makes this clear as well. These facts illustrate the rapid expansion and development of the Pennsylvania colony.

On the 1741 plot of land, Andreas Hagenbuch would build a permanent homestead in the Americas. The survey corroborates this by referring to it as the “Home Tract.” Here, he would construct a home and barn, raise a large family, and live out the rest of his life. The acquisition of this land represented an end to what had been a 4,000 mile journey from civilized Europe to the frontier of Pennsylvania.

The homestead property had several advantages for the Hagenbuch family. First, there were two, small creeks on the property which provided the family with plenty of surface water for irrigating crops, watering livestock, and running a distillery. Second, while the land has some elevation, much of it is suitable for agriculture. Only the southern end of the property is hilly. Finally, the Allemaengel Road—a major route in this region—ran through the parcel. Once the road was improved in the mid-1750s, wagons could more easily access the homestead and transport goods to markets in nearby towns.

After acquiring the tract and erecting a temporary shelter, Andreas and his wife, Maria Magdalena, faced the difficult task of developing the land. The property would have been covered with dense, old growth forests. Clearing these was of critical importance to settlers whose livelihoods depended upon farming. Lumber was needed to construct a house and a barn, while fields were required for crops and pastures needed by livestock.

According to Benjamin Rush (b. 1745) in An Account of the Manners of the German Inhabitants of Pennsylvania, settlers used different methods for clearing land. While the English and Irish, stripped the trees of bark and left them to die and rot, the Germans cut down the trees and labored to remove the stumps from the ground. Rush wrote the following in 1789:

In clearing new land, [German immigrants] do not girdle the trees simply, and leave them to perish in the ground, as is the custom of their English or Irish neighbors; but they generally cut them down and burn them. In destroying under-wood and bushes, they generally grub them out of the ground. By this means a field is as fit for cultivation the second year after it is cleared as it is in twenty years afterwards. The advantages of this mode of clearing, consist in the immediate product of the field and in the greater facility with which it is plowed, harrowed, and reaped. The expense of repairing a plow, which is often broken two or three times in a year by small stumps concealed in the ground, is often greater than the extraordinary expense of grubbing the same field completely in clearing it.

It’s difficult to imagine the staggering amount of time it took to cut a swath out of the wilderness and establish a homestead. Research suggest that settlers cleared around two to three acres of land per year. However, we do have a way of getting more specific numbers. Many 18th-century tax assessors in Pennsylvania noted the acreage of wooded and cleared land on a property. For instance, records shows that John Heil—a settler in Moore Township, Northampton County, PA—cleared his land at an average rate of four acres per year. The same records show that in 1768 Andreas had cleared 50 acres of land. This equals about two acres of land cleared per year.

In 1851, Michael (b. 1805), the great grandson of Andreas, built a beautiful stone farmhouse on the homestead property. Today, this building remains standing. Yet, it’s important to remember that the original house at the homestead would have been a simple, log structure. Glass was a luxury, meaning that windows would have been small and few. Unlike the homes built by the English, German log houses featured a central chimney and stove when possible. These helped to more efficiently distribute the heat from the fire.

While the Allemaengel was sparsely populated in mid-18th century, the Hagenbuchs were not alone in the region. The survey of the 1741 homestead property noted two neighbors: Adam Trum (also spelled Drumm) (b. 1705, d. 1757) and Tobias Stapleton (b. 1717, d. 1805). Both of these names would crop up again in the history of the Hagenbuch family.

In the Allemaengel, homes were separated by significant distances. The Hagenbuch’s property was about 2,270 feet wide—close to half a mile. Many of the adjoining parcels were at least this wide. In other words, if houses were near the center of their parcels, neighbors would have needed to walk a half mile to visit with one another. Forests would have made this distance seem even further.

Andreas Hagenbuch spent the rest of his life on the homestead and was buried there in 1785. He and his family added additional lands to the homestead, eventually growing their holdings to over 300 acres. This land stretched from the rolling foothills of the Allemaengel to the forested ridge of the Blue Mountains.

The Hagenbuch homestead would remain in the family until the mid-1850s. During this time, it passed first from Andreas to his son Michael (b. 1746), then to Michael’s son Jacob (b. 1777), and finally to Jacob’s son Michael (b. 1805). When Michael died in 1855 at the age of 49, his wife Abigail “Apia” (Stapleton) Hagenbuch (b. 1811) and their children were unable to care for the property. Ultimately, the homestead was sold out of the family.

The Hagenbuch homestead has had a lasting impact on the family. Nearly all Hagenbuchs living in the United States can trace their roots back to this rural property in Albany Township, Berks County, PA. Even today, almost 300 years since Andreas arrived in America, a large number of Hagenbuch families live in central and eastern Pennsylvania.

In future articles in this series, we will look at the struggles the Hagenbuchs faced in the Allemaengel, as well as the family’s growth and prosperity.

This article was updated on June 4, 2025 to include additional details about the Hagenbuchs settling on the Home Tract. Images were updated and Andreas’ daughter, Catherine, was removed from the family group in 1738 since she wasn’t born until 1739.

I, too, am a descendant of Andreas Hagenbuch – seventh generation – grow up in eastern Pennsylvania and now live in Cathedral City, CA.

Andreas and his wife were my 6th great-grandparents.

Thank you for creating this website for their descendants.

This was so fun to find and read! It’s so nice to see the history preserved and cherished.

Tobias Stapleton, who is mentioned above, is my 7th great grandfather. My research shows him married to Anna Barbara Hagenbuch.

Hi Christina. Nice to hear from you! We wrote an article which touches upon why the long circulated idea that Anna Barbara Hagenbuch was married to Tobias is likely not correct: https://www.hagenbuch.org/anna-barbara-hagenbuch-rethinking-andreass-children/ There were Hagenbuchs, though, that did marry into the Stapleton line. You can explore a few of those records here: https://beechroots.com/person/search?PersonSearch%5Bfull_name%5D=stapleton

Hi Andrew, it’s great to hear from you and so quickly!

I can’t wait to read your article.

I actually did have her father as Hans Michael, born in Germany, then wondered if that was actually wrong when I read your page.

Thank you so much

for the links and the information!

Hello. My name is Robert Hagenbaugh and I have been completing my family tree on ancestry.com. Andreas is my 7th great grandfather. I live in North East Pennsylvania (Gouldsboro, PA) pocono mountains. I was born and raised in Hanover Township, PA. This is a great website.

Hi Robert. Great to meet you, and I am happy you found our site! Based upon your spelling of the last name and location in PA, it seems like you might be within this family group somewhere? https://www.hagenbuch.org/making-sense-christian-hagenbuchs-family/ If you send us a message via the Contact page https://www.hagenbuch.org/contact-us/ we can chat more. I’d like to learn more about your family line back to our common ancestor, Andreas (b. 1715) and place you on our family tree!