Andreas Hagenbuch Acquires Land in Berks County

Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1715) and his family landed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on September 18, 1737. They spent that first winter in or nearby the city. As spring approached, Andreas Hagenbuch visited the Pennsylvania Land Office at the home of the Proprietors, Thomas and John Penn, in Philadelphia. On March 25, 1738, he received a land warrant for 200 acres of land in what is today Berks County, Pennsylvania.

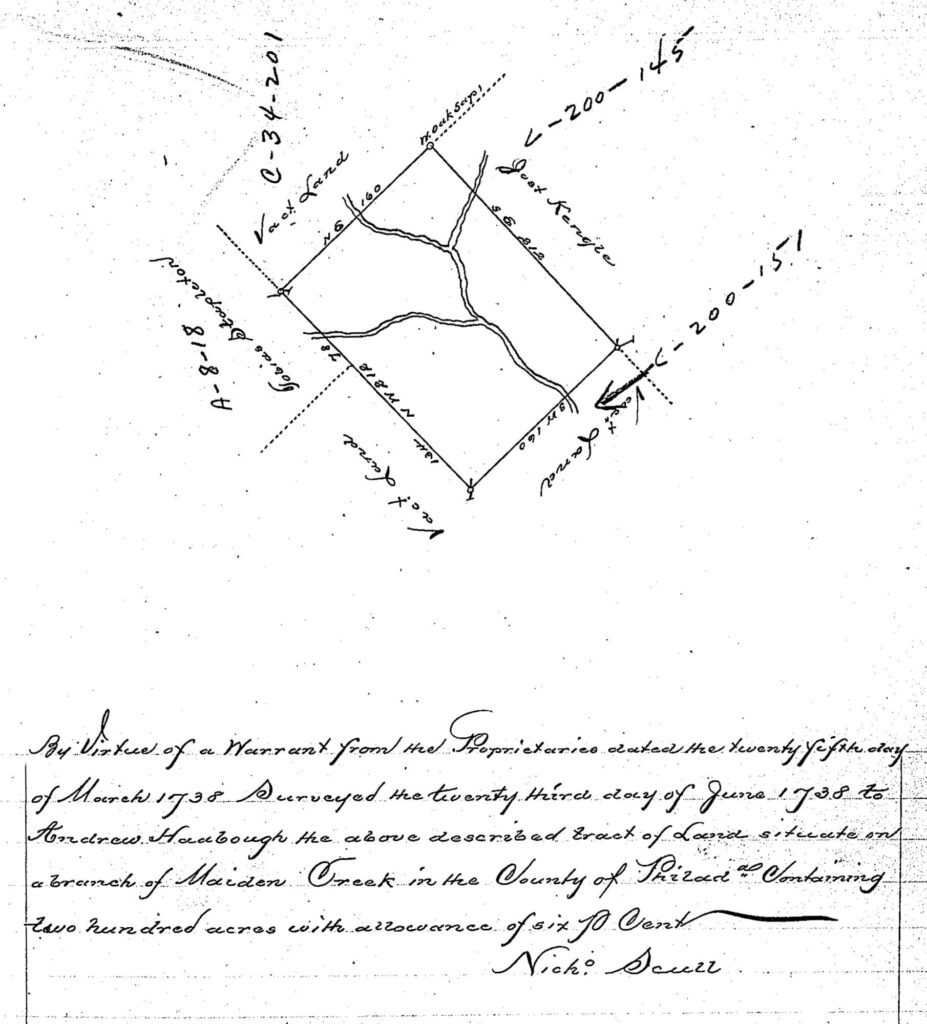

As noted on the warrant, the land was situated on a branch of Maiden Creek. Two of the adjoining parcels had owners: To the west was Tobias Stapleton and to the east was Jost Kengle (possibly a misspelling of Kunkel). The lots to the north and south were vacant.

Andreas Hagenbuch obtained his land warrant while in Philadelphia, without ever viewing the property. According to researcher John Barrett Robb, obtaining a warrant required that settlers first fill out an application for a roughly defined tract of land and pay a fee—typically half of the purchase price. In the mid-1700s, land prices ranged from between £5–15 per one hundred acres (around $1,000–$2,000 in 2025 dollars).

After receiving the warrant, an additional fee was paid to an official surveyor who would travel to the area, survey the parcel, and create a detailed plat map for it. The completed survey was then filed at the land office. Once the remainder of the purchase price for the land was paid, the settler received a land patent. The patent provided full title to the parcel and permitted its ownership to be transferred using a deed.

The Hagenbuchs’ 200 acre lot was surveyed on June 3, 1738 by the noted land surveyor Nicholas Scull II. Scull had participated in the survey of the land that would become the Walking Purchase. Later, he was appointed Surveyor General for Pennsylvania from 1748 to 1761. He was an excellent cartographer and drew many detailed maps of the colony.

As noted earlier, a land warrant did not provide the warrantee with the complete legal title to a parcel. Once Scull’s survey was completed and returned to the land office in Philadelphia, Andreas was expected to visit the land and, if it met to his liking, settle upon it and pay the remainder of the purchase price. Finally, he would be granted a land patent and officially own the property.

Given this costly, multi-step process, not everyone who applied for a land warrant was granted a final patent. Sometimes the original warrantee died and never paid for the patent. Other times, the land warrant was sold to another person and this individual paid for and received the patent. Additionally, some people abandoned their parcels and chose to settle in another location. In all of these cases, the forfeited land warrants were reissued to other settlers.

When Andreas Hagenbuch received a warrant for 200 acres in 1738, Berks County was still part of Philadelphia County. Berks County would not be formed until March 11, 1752. As a result, the location of Andreas’ land was recorded as Philadelphia County.

Locals had a name for the place where the Hagenbuchs’ parcel was situated. They called it the Allemaengel (which was also written as Allemäengle and Allemangel). The original mean of Allemaengel has been lost to time. However, according to an 1886 book, The History of Berks County, Allemaengel was a German phrase meaning “a land wanting in fertility of soil.” Other sources simply state that it means “all wants” in reference to the poorness of the soil in the region. This is odd, given the rich farmland found there!

Why would Andrea Hagenbuch choose to live in a place with such an inhospitable name? One theory is that the meaning of Allemaengel was referencing the lack of cleared farmland, not the fertility of the soil. Certainly, the area was heavily forested and required significant energy to prepare it for agriculture. Another is that Andreas Hagenbuch may have known people living there and, therefore, knew Allemaengel to be a misnomer.

One final theory is that the word Allemaengel had nothing to do with the quality of the land. Instead, it described the ethnicity of the people living in this area. The French call Germany the Allemange. Might Allemaengel actually refer to high concentration German immigrants who settled in this region of Pennsylvania?

After receiving a warrant for their land, we can imagine Andreas and Maria Magdalena (Schmutz) Hagenbuch, along with their infant son, Henry, setting off for the Allemaengel in the spring of 1738. Their journey would have been a difficult 75 miles. There were few decent roads outside of Philadelphia and even fewer maps of Pennsylvania’s frontier regions.

In his book The Pennsylvania German Farm, Amos Long Jr. writes:

While still in Philadelphia, the settlers had to arrange for their land warrant. Those warrants were a source of much misunderstanding, for the settlers had earlier understood them as being title to their land, and didn’t realize that later they had to pay for them! After they received their warrant, the pioneers purchased a wagon and team, or a few pack horses or mules, or even oxen, loaded their worldly goods, and set out for the Allemäengle. To get there, they had to cross a barren, swampy wasteland of scrub oaks called Long Swamp, then through the Rittenhouse Gap in the South Mountain, northward to the Schochary Hills. They traveled the tops of the ridges because the valleys were full of vines, mosquitoes, and swamp fever. Arriving at their warrant, they set up a camp-site, usually a small lean-to, at a spring near the protected land of a low valley. Sometimes the wagon was the only shelter for the first several months until a cabin could be constructed.

While the above passage provides a number of key details, the Hagenbuchs’ exact route to the Allemaengel isn’t entirely clear. From Philadelphia they likely headed in a northwestern direction, along a route to the west of modern Interstate 476. This would have taken them through Long Swamp and Rittenhouse Gap—an area found between Allentown and Kutztown. The Schochary Hills are to the north, near present day New Tripoli. The Hagenbuchs’ land parcel is about five miles to the west of the town.

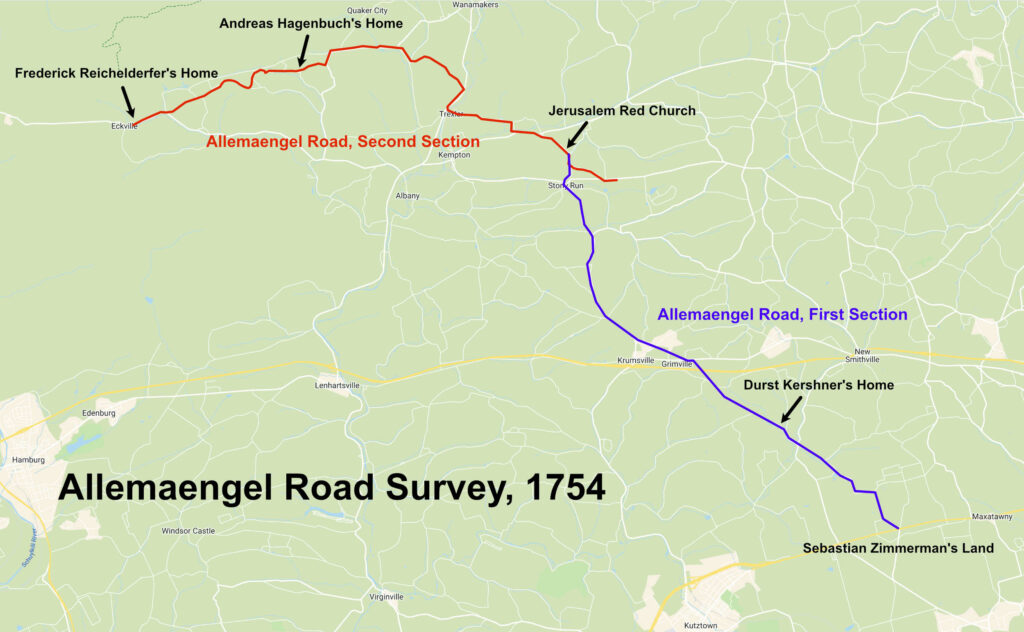

An important route through the Allemaengel was officially surveyed by Berks County in 1754. This survey showed that the road began just west of present-day Maxatawny, PA and traveled in a northwesterly direction towards the town of Kempton, PA. From here, it turned west until it terminated near Eckville. It is quite possible that this route existed in some form when the Hagenbuchs settled here in 1738.

This map shows the eventual site of Andreas Hagenbuch’s home—where he settled by 1741. Andreas’ original 1738 land warrant is about where the word “Home” is in the label “Andreas Hagenbuch’s Home.”

Today, this area is mainly farmland nestled at the foot of Pennsylvania’s Blue Mountains. Seeing the rolling fields, it’s difficult to imagine the wilderness that faced Andreas Hagenbuch and his family in 1738. These were frontier lands covered with dark forests, full of wild animals, and populated by American Indians. There was much to fear.

According to J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur (b. 1735, d. 1813) in his Letters from an American Farmer:

Reaching a settlement is like a feast for an inexperienced traveler—to see sun shine on some open grounds, to view clear fields. You seem to be relieved from that secret uneasiness and involuntary apprehension which is always in the woods.

It was also sparsely populated by Europeans. German Lutheran minister Henry Muhlenberg (b. 1711, d. 1787) wrote the following about traveling through Pennsylvania in the 1740s:

When one travels on the roads, one constantly travels in bush or forest. Occasionally, there is a house and several miles down the road there is another house.

Settlers preferred land that was near a road and had water on the property. On paper, Andreas Hagenbuch’s parcel looks like it fits the bill. The 1738 survey shows a creek branching over the 200 acres. Unfortunately, this may have caused problems for the family. While researching the 1738 parcel, my father, Mark, and I visited the location of it in Albany Township, Berks County, PA. The property is primarily a low field with several small creeks running through it. It also appears to be somewhat swampy.

We can imagine the Hagenbuchs arriving in the Allemaengel only to discover their parcel wasn’t what they had imagined for their homestead. Perhaps, they tried to hack out a living there for a year or two while they explored the area and searched for other open land. Alternatively, they may never have settled upon the parcel and immediately found another one nearby to squat upon until they applied for another warrant.

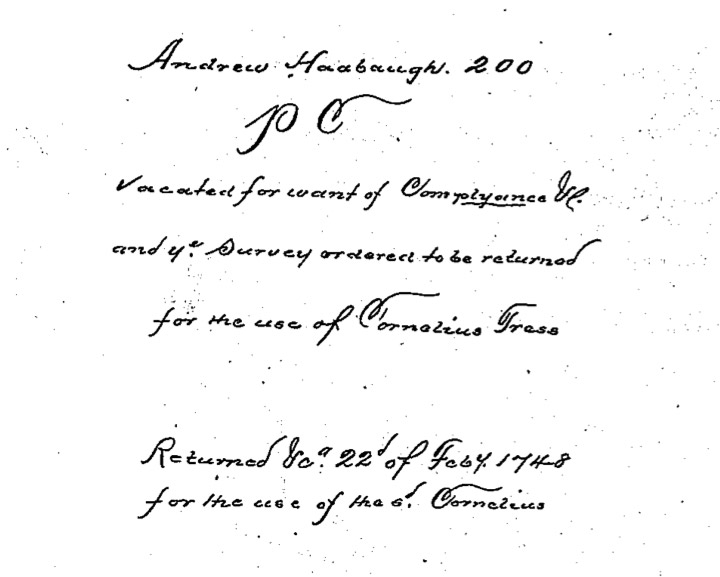

Whatever the reason, we know that Andreas and his family vacated their first warrant by November 4, 1741. On that date, Andreas Hagenbuch received a new warrant for 150 acres about a mile west of his previous warrant. On this tract of land, he would finally build his homestead, raise a family, and live out the remainder of his life.

Andreas Hagenbuch’s 1738 warrant for 200 acres was returned to the land office in 1748 for lack of compliance. It was then given to a new warrantee, Cornelius Fress (a misspelling of Driess or Dries). In the next article in this series, we will explore the 1741 land parcel which is the site of the Hagenbuch Homestead.

This article was updated on May 6, 2025 to include more details about the 1738 land warrant, additional pictures and maps, specifics on how the land was acquired, and links to other key articles.

Allemangle means “all wants” meaning the land has “all that a man could want” such as in fertile soil.

I live on the site of this land, and it is extremely rocky. Pioneer settlers probably spent a few decades spreading manuer and whatever to eventually make it a decent farm area, but I never knew any farmers here who made decent money farming this land. Albany and such really does refere to a very needy / rocky soil.

Hi Ron. For some reason, I never saw this message three years ago! Are you indicating your live on part of the original 200 acre parcel once owned by Andreas Hagenbuch? I’m interested in learning more.

It was not about making money in 1738. The settlers were fleeing religious oppression in their their homeland following the Edict at Nantes. These Germanic folks,however also ,recognized natural beauty and wanted to minimize “heimweh” or home sickness.sot they were attracted to areas that were reminiscent of parts of Switzerland, Alsace and the German Palatinate.The Allemangel is reminiscent of these regions to this very day.

The land parcel of 1741…is the homestead building still there?

Hi Linda. There is a house there, although it was built later—by Andreas Hagenbuch’s great grandson. The location of the original homestead is discussed in this series of articles if you are interested! https://www.hagenbuch.org/tag/house-along-the-allemaengel-road-series/