Thoughts on Christian Hagenbuch’s Last Will and Testament

Christian Hagenbuch was born on December 17, 1747 at the Hagenbuch Homestead in present-day Albany Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania. Back then, Albany Township was on the frontier and still part of Philadelphia County within the Pennsylvania Colony. Christian was the fifth child and third son of Andreas Hagenbuch (b. 1715). His mother was Anna Maria Margaretha (Friedler) Hagenbuch.

As a boy, Christian helped his family on the farm. He may have learned to operate a distillery at the homestead. In 1773 his father, Andreas, purchased 155 acres of land in East Allen Township (then Allen Township), Northampton County, PA. Christian moved to that parcel and built a distillery there. He married Susanna Dreisbach (b. 1756) around 1775 and they started a family. From 1778 to 1780, he served in the Northampton County Militia and fought in the Revolutionary War.

In 1782, Andreas sold 149 acres of his land to Christian and in 1783 Christian built a new stone house there. Tax records show that in 1789 Christian was running a distillery on the property that had several stills, suggesting a reasonably-sized operation. He acquired other land in Northampton County and even a parcel in Columbia County in 1809.

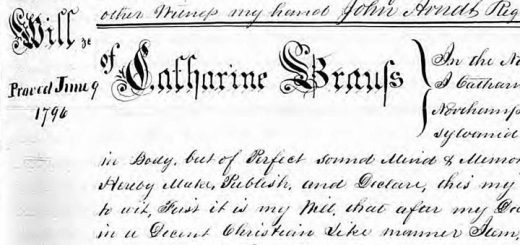

On January 25, 1812, Christian Hagenbuch died at the age of 64. He is buried beside his wife, Susanna, at Zion Stone Church Cemetery in Kreidersville, PA. He dictated his will on January 16th, nine days before he died. While having a will might not seem noteworthy, many early Hagenbuchs died without one, such as Christian’s two older brothers, Henry (b. 1737) and Michael (b. 1746).

Christian’s will begins by describing that he is “sick and weak in body” suggesting that his health was failing due to disease. At 64 years old, he was six years younger than his father Andreas when he died. His brothers Henry and Michael died at ages 67 and 62 respectively, while his youngest brother, John (b. 1763), lived to the ripe old age of 82. Certainly life on an 18th century farm was difficult, but his brother Henry ran a tavern in what is now Allentown, PA. Might there have been another factor hastening their deaths like genetics? We simply don’t know.

Next, Christian provides for his wife, Susanna, whom he calls “Susan.” He describes how she should have the back room on the first floor of their house as her own. He then ensures she has plenty of food and drink including wheat, rye, Indian corn, buckwheat, coffee, sugar, tea, pork, beef, tallow, flax, potatoes, apples, garden truck (fresh vegetables), distilled spirits, wine, and “cyder.” In addition, she is provided shoes, apparel, a stove, cows, plenty of firewood “laid down at her door”, household furniture, and a servant girl to wait on her, a doctor when needed, and 218 pounds money.

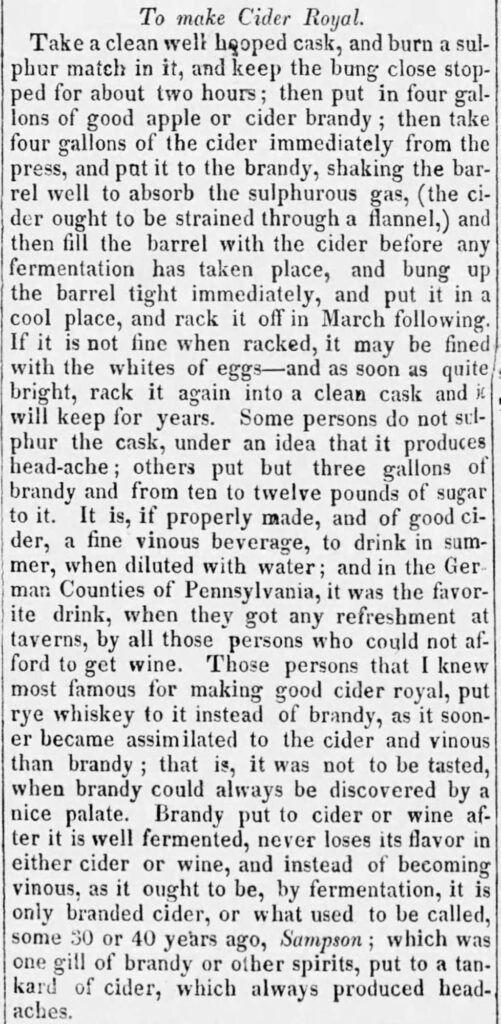

A few things stand out here. First, Christian is very specific in what he provides for his widow. In the early 1800s, women had little right to their husbands’ estates. Without his expressed will, Susanna might received nothing after Christian’s death. Then he states that she should receive “cyder.” This is almost certainly cider royal, a drink made by fortifying hard cider with apple brandy. Lastly, Christian designates all monetary sums in his will as pounds rather than dollars. Indeed, it wasn’t until 1857 that foreign money was outlawed as legal tender in the United States. It could be that Christian preferred British pounds due to the instability of the early U.S. banking system. Ultimately, it appears that he gave his wife about $25,000 in today’s dollars.

Christian bequeathed his landholdings in Allen Township to his sons Andrew (b. 1782) and Joseph (b. 1795). According to the will, he owned a second farm of 57 acres near his primary parcel of 149 acres.The brothers received the land and everything on it, including a profitable distillery. They would operate this until 1823, when it went bankrupt and was sold out of the family.

Beside his sons Andrew and Joseph, Christian gave to his other children too. Maria “Polly” Magdalena Hagenbuch (b. 1776) received 166 pounds, 13 shillings, and 4 pence, which is equivalent to around $20,000 today. His daughter Anna “Mary” Maria (Hagenbuch) Coleman (b. 1779) was given twice this amount; his son John (b. 1785) got three times this sum; and his daughter Elizabeth (Hagenbuch) Deshler (b. 1788) was provided four times this amount.

But Christian wasn’t done. He next specified additional amounts for certain children. Andrew was given 200 pounds. Polly received 125 pounds and another 500 pounds paid with two cows, two bedsteads, bed and bedding, one dresser, six chairs, a table, corner cupboard, and a saddle with bridle. Mary got 500 pounds minus what her husband, John Coleman, owed Christian plus interest. John was given 500 pounds minus what he owned his father. Elizabeth received 100 pounds and another 500 pounds paid with two cows, two bedsteads, bed and bedding, one dresser, six chairs, a table, corner cupboard, and a saddle with bridle.

It is likely that Joseph wasn’t included in this section because he was only 17 years old and a minor. Polly and Elizabeth each received their 500 pounds as items required for setting up a home. Unlike their sister Mary, these two were unmarried and would have needed to own furniture and bedding.

In the final part of the will, Christian asks that a lot he owns be used as a fund to pay Susanna, Andrew, Polly, and Elizabeth. Research shows that the lot was sold to Jacob Deshler who married Elizabeth Hagenbuch in 1813. The couple built their home on this lot before later relocating to Northumberland County, PA. Today, that house stands at the corner of Weaversville Road and Walnut Street in Northampton County.

House built by Jacob and Elizabeth (Hagenbuch) Deshler on property once owned by Christian Hagenbuch

Christian appointed his son, Andrew, and his friend, John Weaver, to be the executors of his will. He had friends John Hower and Thomas McKeen witness the documents signing too. Most of these men were part of the Franklin Society, which debated for fun in the early 1800s. It’s clear that the Hagenbuchs were part of a tight-knit community.

The last will and testament of Christian Hagenbuch illustrates how he cared for his children and wife after his death. It also demonstrates that he led a successful life, raising a family as well as running a farm and distillery.

When my father, Mark, and I began our collaboration on Hagenbuch genealogy, we believed Christian was the “black sheep” of Andreas Hagenbuch’s sons. A decade of research has shown otherwise. Christian, along with his older brother Michael, were the primary heirs to their father’s estate. They embodied many of his hopes for the future of the Hagenbuch family in America.

Thank you so much for the history and genealogy of Christian Hagenbuch and family. It was comforting to learn of his life being commendable in the Hagenbuch hierarchy! God’s peace to all in 2026!