Butchering Day Memories from the Farm, Part 2

This article is a continuation of the first part in the series, Butchering Day Memories from the Farm. In it, we got started with the pig butchering process: killing the hog, sticking it to bleed it out, scalding it in a huge wooden vat which loosened the hair, and scraping it. The hog is hung, split, and gutted. Cuts of meat are separated on the butcher tables, while hot water is boiling in a kettle. The organ meats and other scraps are boiled down in water for puddin’ and then scrapple.

Along with the huge kettle that cooked the scrapple from puddin’ made from organ meats was another kettle for the lard. The hide of the hog, made up of its tough skin and fat underneath, is cut into chunks and thrown into a kettle. Eventually, the fat separates from the skin which gets crispy. What’s left is hot, liquid fat (when cooled and solid it is lard that is just right for doughnuts!) and “cracklins.” City folk today would liken these to the pork rinds that one buys in the grocery story.

However, cracklins are nothing like pork rinds. They are hard and sometimes streaked with a hint of meat. Once in a while, cracklins contain some fried pig hair that was not completely scraped off after scalding. When I was a boy, we would eat cracklins and be thrilled when there was a bit of hard meat running through it, and we would laugh when we got some hair in our mouths. Pig hair sometimes shows up in the scrapple too. The joke was it held the scrapple together better!

When I think of cracklins, it brings to mind the two old men who lived on the back end of our farm. George and Elmer burned lime at the kiln that was owned by Royer’s Quarry during the 1960s. George was tall and Elmer was short; they were always covered in lime dust and dirt. They were grizzled old men, unshaven, who had seen too much hard work in their day.

Soon after butchering day, they would show up at our door. Mom—Irene (Faus) Hagenbuch (b. 1920)—would take an old cloth flour bag and fill it half full with cracklins and give it to the men. I can still see them trudging up our snow covered sledding hill back to their shack beside the lime kiln, the grease from the cracklins staining the flour bag.

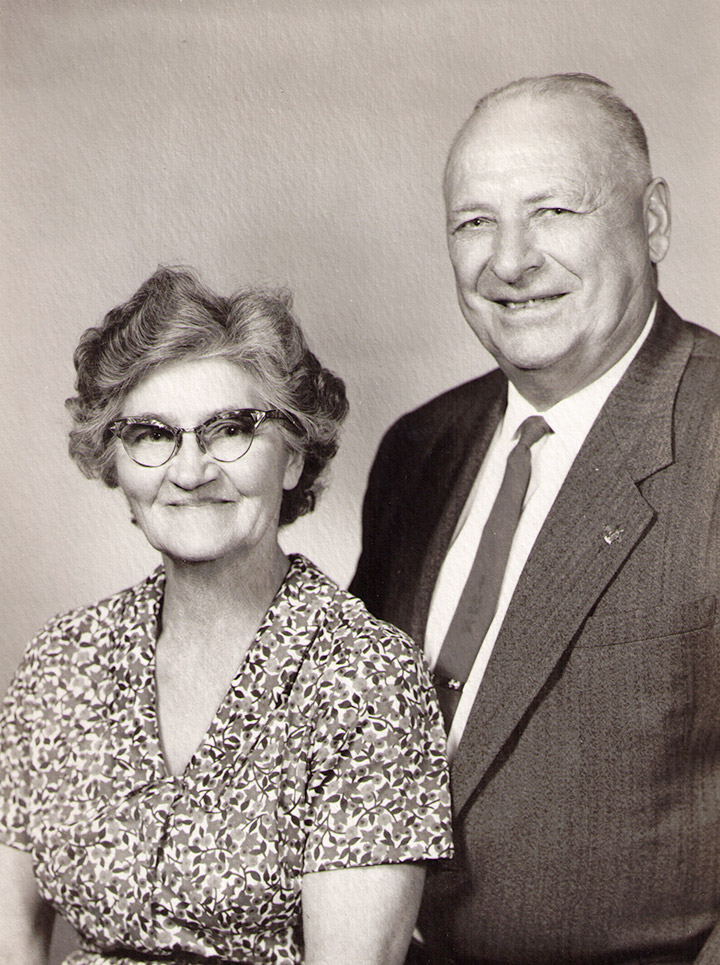

Grandma Faus (Minnie Mary [Hilner]) and Grandpa Faus (Odis Guy), maternal grandparents of Mark O. Hagenbuch

Barb cannot remember any other women coming to help fix the mid-day meal. It was a lot of cooking for about 10 people. I do remember that we would sample the liver fresh out of the boiling kettle along with tasting the scrapple and puddin’. Maybe that helped to stem the men’s appetites.

Barb continues that it was an exciting day and started very early. It was also cold! Someone shot the pigs, then they were scalded in the vat, scraped, and hung up on the tripods. She remembers the long tables in the shanty, cutting the fat into chunks, and boiling it in kettles.

The cracklins were dipped out and put through a press to get all the hot fat out of them. Barb likens the cracklins to crisp potato chips. She remembers there was a lot of joking and laughing among the men. The men would tease us kids by threatening to pin the pig tails on us, and I remember them also chasing us with the cut off pig ears.

Along with all the cooking that Mom had to do that day (with Barb’s help), there was the cleaning of the pig intestines for sausage casings; a dirty job which Mom only did for a few years as later she would buy casings for the men to use on the press to make sausages.

Our family did not clean and use the pig stomachs for hog maw. I do remember Dad—Homer S. Hagenbuch (b. 1916)—saying that Grandpa Faus would always get these and clean them as he was a fan of filled stomach. Along with a recipe for scrapple, there was a recipe for sausage, just the right amount of pepper and spices. Then, we would smoke the sausage and hams in our smokehouse, which was located near the shanty. Harold Sechler always said that apple wood was the best for smoking.

In 2001, we made arrangements to butcher two hogs with Dale and Lamar Rathmall, who were members of my father-in-law’s—Reverend Roy A. Gutshall (b. 1920)—congregation at Delaware Run Lutheran Church near Dewart, Pennsylvania. My wife Linda and our three children showed up at their farm very early on a January morning, and I got to relive the butchering days of my youth.

My children remember the smells, cold, and hard work of that day, especially my son Andrew and his accompanying friend Nathan Hoover, both of whom were about 20 years old. We did all the tasks associated with butchering: scalding, scraping, cutting lard and bacon, boiling the cracklins, making puddin’ and scrapple.

While we worked, I commented to the Rathmall brothers that they sure had good equipment to work with. They told me that they had purchased all the equipment from a fellow near Limestoneville whose cousin had been a master butcher and had died a few years before. The seller’s name was Dad’s first cousin, Harold Sechler; and the master butcher was none other than cousin Myron Cromis. Most likely, the butchering equipment I was using that day was the same equipment that had been used on our farm in Montour County in the 1950s and 60s. History comes full circle!

This article was updated on August 12, 2025 to include additional pictures, improved formatting, and additional details.

Mark –

Thank you so much for these wonderful memories. Irene Faus Hagenbuch is my third cousin – we both descend from Thomas Faus, born in 1803. Although I was born in Lancaster, I missed out on all of those Pennsylvania Dutch traditions.

Great story. The quarry was owned by LaRue Royer, not the Narehood’s. Myron Cromis helped my grandfather, Clyde Marr butcher at his farm until my grandfather retired. Then, Myron built his butcher shop at his farm. As a child, I can remember staying home from school on some of the butchering days. Grandpa butchered throughout the week during the Fall and Winter months. There were always the same four men butchering, my grandfather, Clyde Marr, Elwood Cotner, Zender Young, and Myron Cromis.

Hi John. Thanks for this memory and for posting this! One question: is it that the quarry was sold by the 1960s (which is the time period Dad is referring to in the article)?

George and Elmer worked at Royer’s lime kiln, which was part of the Huttenstein Farm (spelling may be wrong) LaRie Royer was married to Huttenstein’s daughter. This would be the next farm on the same side of yhe road towards Limestoneville, from the Hagenbuch farm. My grandfather, Foster Narehood sold Narehood Brother’s stone quarry in 1956 or 1957 to Lycoming Silica and Sand. LaRue Royer opened his second quarry on Royte 254, not sure on the year. Royer’s quarry on Route 254 was later sold to the company that owned my grandfather’s old quarry. Royers first quarry and lime kiln grounds is still in the Royer family, Don has his home there and is one of LaRue’ sons.

Thanks, John, for confirming and for the additional details! I’ve edited the piece to reflect that they worked a Royer’s not Narehood’s. I appreciate your insights in making sure Dad’s memories are as accurate as possible for future generations 🙂