Flying with Honor: Major Glenn E. Hagenbuch, Part 2

By the end of 1942, Captain Glenn Everett Hagenbuch (b. 1918)—a farm boy from Illinois—was stationed in England with the Army Air Corps. (Read Part 1 in this series to learn about Glenn’s early years.) Back in the states, he had earned his pilot’s wings and learned to fly the B-17 Flying Fortress. Now all of that training was being put to the test in the skies over Nazi-occupied Europe.

1943 began with Glenn being appointed commander of the 427th Bomb Squadron of the 303rd Bomb Group. The promotion came after squadron leader, Major Charles C. Sheridan, was killed while flying a B-17 over St. Nazaire, France on January 3, 1943. Glenn immediately rose to the challenge and led new bombing missions over France with targets in Lille on January 13th and Lorient on January 23rd. Soon they were dropping bombs inside Nazi Germany, and on February 14th targeted industrial facilities in the city of Hamm.

One of the most dangerous missions occurred on February 26, 1943. Glenn, as the squadron’s commanding officer, piloted the lead B-17 over Wilhelmshaven, Germany to bomb the naval base there. This particular mission was unique for another reason too. It included members of the Writing 69th—an informal group of news corespondents reporting on the war. Tired of sitting in offices while thousands of young men died in battle, the group’s members volunteered to go to the front lines and compile first-hand accounts of what they experienced.

Glenn Hagenbuch’s B-17 flew one member of the Writing 69th, a young reporter named Walter C. Cronkite (b. 1916). Cronkite would eventually become a household name as the anchorman for the CBS Evening News. But, in early 1943, he was just another reporter trying to make a name for himself. All that would change with the front page publication of his piece about the bombing of Wilhelmshaven.

Walter C. Cronkite (fourth from left) with journalists from the Writing 69th as they prepare to fly on a bombing mission, 1943. Credit: Wikipedia.org

Titled “Hell 26,000 Feet Up” in the New York Times, the article opened with the following:

At a U.S. Flying Fortress Base Somewhere in England, Saturday, February, 27. — American Flying Fortresses have just come back from an assignment to hell, a hell 26,000 feet above the earth, a hell of burning tracer bullets and bursting gunfire, of crippled Fortresses and burning German fighter planes, of parachuting men and others not so lucky.

Cronkite continued with a play by play of the battle over Wilhelmshaven, even mentioning Glenn at one point:

We had our share of enemy fighters. About 10 were almost constantly within attack range throughout the two-hour fight. With scarcely a pause someone on the ship was calling out over the inter-communication phone the position of an approaching enemy.

“Six o’clock low.” “Four o’clock high.” “Two o’clock high.”

“The – – – – is coming in.” “Get on him! Give him a burst. Keep him out there.”

As our guns shook the plane, the voice of the skipper. Capt. Glenn E. Hagenbuch, 24, of Utica, Ill., rang out:

“That’s scaring him off, boys. He won’t be back for a while. Nice work.”

But Hagenbuch’s words of congratulation were chopped off when another of our gunners called:

“Ten o’clock high. He’s coming in.”

By many accounts, “Hell 26,000 Feet Up” was the dispatch that captured the attention of the American public and launched Cronkite’s career. It grew Glenn’s reputation as a pilot too, exhibiting his calm demeanor and skilled hand under the most dire of circumstances. His leadership led him to receive the Air Medal on February 1st for “meritorious achievement in aerial flight” along with three Oak Leaf Clusters. He was officially promoted to Major on March 30, 1943.

All the while, the perilous missions over Europe continued. On March 4th, Glenn flew in a bombing mission over Rotterdam, Netherlands followed by Rennes, France on March 8th; Amiens, France on March 13th; Vegesack, Germany on March 18; Paris again on April 4th; Bremen, Germany on April 17th; Meaulte, France on May 13th; Heligoland Island, Germany on May 15th; and Kiel, Germany on May 19th. He flew all of his missions with the 427th Bomb Squadron in the 303rd Bomb Group, except for one. On June 22nd, Glenn’s plane joined the 384 Bomber Group as part of a special task force to attack Antwerp, Belgium.

Major Glenn E. Hagenbuch completed his 25th B-17 bombing mission on June 29, 1943. The raid on Paris marked his successful completion of a 25 mission combat tour. A picture celebrating the momentous achievement captured a smiling Glenn surrounded by his crew. Yet, instead of returning to command for a desk job, Glenn participated in a special mission to North Africa. This may have been to ferry B-17s to airfields, as well as train pilots for future bombing missions. The Allies had driven the Nazis from North Africa in May of 1943 and were now preparing to launch the campaign to retake Italy.

After the special mission ended, Glenn was stationed in England as part of the 8th Bomber Command. He took on a supporting role, training pilots and testing planes. In early September, it was announced that he had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his successful piloting of 25 bombing missions and a Silver Star with Oak Leaf Cluster for “directing a heaving bombardment wing from his position in the leading plane of the formation.” On September 24th, he wrote to his parents with the news and explained that he had been offered the rank of lieutenant colonel but was declining it because he had “just enough rank to realize the ambitions of years past.” He ended his last letter home with: “Get the upstairs room ready; I have plans.”

On October 9, 1943, Glenn was flying a P-40 Warhawk east of Cheddington, England. The plane had recently been worked on, and he was testing it for airworthiness. Witnesses reported hearing the plane’s engine sputter and seeing the aircraft go into a downward spin. The pilot recovered control briefly before the horizontal stabilizers tore off and the plane crashed into the grounds of the Whipsnade Zoo around 10:10AM.

Eyewitness Philip Bates told investigators:

… I heard an aeroplane which appeared to be in trouble. I looked up and saw smoke also flames from from the plane. I also saw some pieces fall off the plane. It then disappeared from my view behind the trees.

Another witness, Pilot Officer Clarke, stated:

I saw an aeroplane crash in the front of the gardens of the Land Army Hostels opposite the “Chequers” P.H. I ordered my driver to stop and took out my fire extinguisher, ran into the garden and found the pilot lying about 2 ft from the plane, having been thrown out. With assistance I dragged him clear from the plane which had burst into flames.

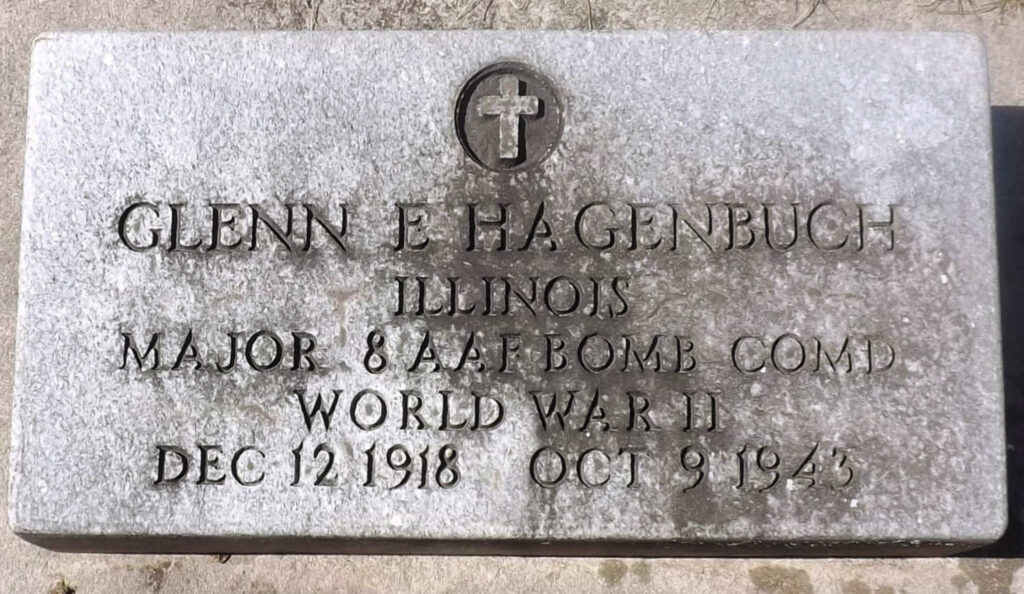

Glenn E. Hagenbuch was killed upon impact. Because the United States was currently at war, his remains were temporarily interred at the U.S. Military Cemetery in Brookwood, England.

On October 16, 1943, the War Department sent a letter to Charles G. and Cora (Bartlett) Hagenbuch, notifying them of their son’s death. The letter mentioned that a telegram about Glenn’s death had already been transmitted to his wife, Margaret (Spaeth) Hagenbuch, in Pocatello, Idaho. The Hagenbuchs were shocked and heartbroken upon hearing the news. However, learning that Margaret was informed first and realizing that she would have control of his estate, simply added insult to injury. Recently, the Hagenbuchs had found out that Margaret was not entirely faithful to Glenn.

Letters from the time suggest that in the summer of 1943, Margaret became pregnant to Richard “Dick” Batley (b. 1919) of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania and that she hoped to leave Glenn for Dick. Glenn may have known about this prior to his death, and his parents certainly knew of it by the fall of 1943. Charles and Cora Hagenbuch wanted to ensure their son received a family burial and was honored by those who faithfully loved him. They hired a law firm to remove Margaret’s claim on Glenn’s estate and remains.

Glenn E. Hagenbuch (left) stands with singer Frances Langford and actor Bob Hope in England, June 6, 1943. Langford and Hope were part of the U.S.O. Troupe during World War II.

While investigating the case, the law firm discovered that Margaret’s marriage to Glenn was illegal. An Idaho marriage license showed that Margaret LaVerne Spaeth (b. 1923) married Jack Quincy Robertson (b. 1918) on May 24, 1942 in Boise County, ID. This was shortly before she met Glenn and only three months before she married him in Battle Creek, MI—all while she was still married to Jack. A judge in Idaho Falls officially annulled Margaret’s marriage to Glenn in 1944.

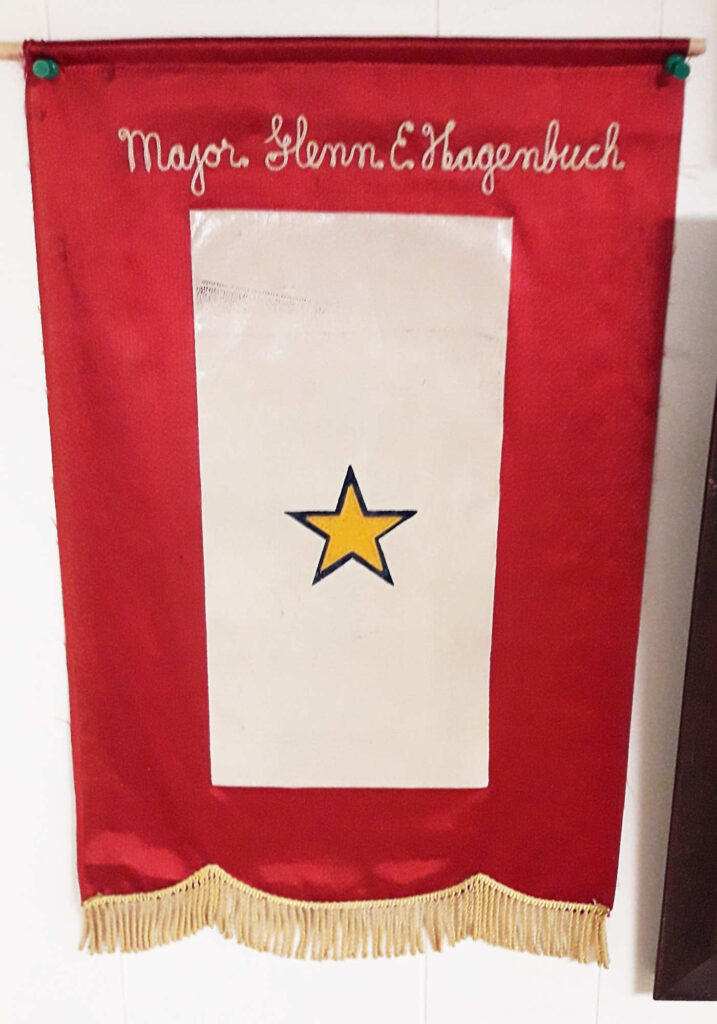

Charles and Cora Hagenbuch were appointed Glenn’s next of kin, giving them control of his estate and possessions. In 1947, after the conclusion of World War II, Glenn’s remains were disinterred and transferred to his parents through the United States’ Return of the Dead Program. A memorial was held, and he was reburied in the Hagenbuch family plot in Waltham Cemetery, LaSalle County, Ill.

Gravestone of Major Glenn E. Hagenbuch, Waltham Cemetery, LaSalle County, Illinois. Credit: Findagrave/Mr. Tink

Glenn’s relatives have never stopped remembering him. In fact, just last year his nephews Mark Strong and David Hagenbuch traveled to England to participate in a special event honoring the uncle they never knew. The ceremony included a church service, as well as a ceremony at the site where Glenn’s plane crashed.

In 24 short years, Glenn Everett Hagenbuch grew from a mid-western farm boy, to an aspiring pilot, to a seasoned combat veteran, to a decorated officer. He was respected by his peers, recognized by his superiors, and loved by his family. Glenn led an honorable life. Through selfless service to his country, community, and family, he demonstrated what can be achieved by helping others. One can only imagine what he might have gone on to accomplish had he survived the war.

In 1997, Melvin Hagenbuch wrote a letter to Walter Cronkite about his brother, Glenn. Cronkite responded:

He was a great fellow and had a lot of good buddies at the 303rd, all of whom had celebrated his survival of his bombing missions—and he was on the toughest raids of that difficult first year in England. Needless to say, we all were hard hit by his demise in what compared to risk-free civilian flying.

Cronkite went on to answer several of Melvin’s questions. He concluded the letter with the following:

I was pleased to hear from a brother of a man I greatly admired.

Today, Glenn is still greatly admired—to say the least.

Wow ! Glenn was a true hero ! Wonderfully written Andrew ! Thank You !

This is an amazing story of a true hero! I am not afraid to admit that I cried. Thanks, Andrew, for another great story about our family.

Thanks, Uncle Bob and Aunt Barb. It is a powerful and moving story!

My dad was responsible for filing and cataloguing aerial recon photos for the 8th Air Force in England. He never talked about the flight crews he knew, for many heroes did not survive.

Neat site! My g-g-g grandma would be Sarah Hagenbuch Newcomer. After that my lineage turns to Larson and then Newman.